Sustainable Development Goals 15

January 2023

To prevent the loss of existing indigenous vegetation and increase indigenous vegetation habitat in biodiversity depleted environments to a minimum of 10% land cover by 2030.

ACHIEVING OUR TARGET

MEANS THAT:

Our land is restored, our water is clean, and our native vegetation and flora and fauna thrive.

Global Picture

Three-quarters of the world’s land surface has been significantly altered by humans. The extent and condition of the world’s ecosystems have declined by an average of 47% compared with the natural baseline, and some are faring worse than others. For example, 87% of the world’s wetlands are estimated to have been lost between 1700 and 2000 and the remainder are disappearing at a rapid rate. Furthermore, terrestrial biodiversity hotspots (regions with exceptional concentrations of species richness and endemism which are under threat) are suffering greater reductions in extent and condition and faster declines than other regions on land. For example, tropical forests, which are the most biologically diverse ecosystems on land, were reduced by 32 million ha between 2010 and 2015.

Around 1 million animal and plant species are now facing extinction. This includes 41% of amphibians, 38% of marine mammals and 33% of reef-forming corals, which are the three worst-hit groups. Current extinction rates are much higher than the average extinction rates in the absence of humans, and in the best-studied taxonomic groups the rate has been accelerating in the last 40 years.

The size of vertebrate populations decreased by an average of 58% between 1970 and 2012 and at least 680 vertebrate species have become extinct since 1500. Almost 600 seed plants (flowering plants, conifers and other seed-producing plants) have become extinct in the last 250 years, predominantly from biodiversity hotspots and tropical islands (Humphreys et al. 2019), a pattern that mirrors the decline in animal species.

The pollinators on which many wild and cultivated plants rely are also affected, with a rapid decline in insect pollinators having occurred in some places and around 16% of vertebrate pollinators, such as birds, bats and monkeys, being threatened with extinction (Potts et al. 2016). People are also failing to safeguard the genetic diversity of cultivated plants and farmed and domesticated animals (and their wild relatives).[1]

The world’s forest area continues to decrease but at a slightly slower rate compared with previous decades. The proportion of forest area fell from 31.9 per cent of total land area in 2000 to 31.2 per cent of total land area in 2020. Despite the overall loss of forest, the world continues to progress towards sustainable forest management.

Between 2010 and 2020, the share of forests under certification schemes, the proportion of forest within a protected area and the proportion of forests under a long-term management plan increased globally.

Safeguarding key biodiversity areas through the establishment of protected areas or other effective area-based conservation is an essential contribution towards Sustainable Development Goals 14 and 15. Globally, this coverage of marine, terrestrial, freshwater, and mountain key biodiversity areas has increased from about one quarter of each site on average covered by protected areas 20 years ago to nearly half of each site covered in 2021.

Vegetation coverage of the world’s mountains remains roughly stable at approximately 73 per cent since 2015. Disaggregated data by mountain class shows that green cover tends to decrease with mountain elevation, evidencing the strong role of climate in mountain green cover patterns.

By February 2022, 129 countries had committed to setting their voluntary targets for achieving land degradation neutrality, and in 71 countries, Governments had already officially endorsed those targets. Overall, commitments to land restoration are estimated at 1 billion ha, out of which over 450 million ha are committed through land degradation neutrality targets[2].

Aotearoa | New Zealand Picture

The current state of much of Aotearoa | New Zealand’s biodiversity demonstrates a trend of ongoing decline. The extent of this decline is variable within and between domains, ecosystems and species.

The major decline in many indigenous land-based species, and in some case their extinction, is largely the result of the substantial reduction in the extent and quality of natural habitats, the impact of introduced predators and herbivores and the legacy of past impacts (including harvesting). Indigenous vegetation continues to disappear with landuse change and intensification. While rates of loss have slowed in recent times, less than half of Aotearoa | New Zealand’s land area now remains in indigenous vegetation cover.

Of the nearly 11,000 terrestrial species assessed using the Aotearoa | New Zealand Threat Classification System (NZTCS), 811 (7%) are ranked as ‘Threatened’ and 2416 (22%) as ‘At Risk’. Between 2012 and 2017, population declines were recorded for 61 vascular plant species. Some threatened plants are key structural species for ecosystems, so their declines can have significant ramifications for their associated ecosystems. However, positive changes have been recorded for other species. For example, the conservation status of 23 land bird species improved between 2008 and 2019 as a result of population increases resulting mainly from conservation management.[3]

Waikato Picture

Concern for the Region’s biodiversity loss lead to the establishment of the Waikato Biodiversity Forum in 2002. The Forum’s Restoring Ecological Priorities and Actions document (2018) noted that the Waikato is one of the regions with the greatest indigenous biodiversity loss in Aotearoa | New Zealand. While indigenous vegetation still covers 25 per cent of its former area in the region, it is concentrated in large patches gracing prominent peaks or fringing ranges. Indigenous forests, scrub and wetlands on the extensive lowlands have been almost completely removed or drained over time, leaving vast expanses without indigenous character. Along the coast, very few of our region’s beaches are undeveloped.

To restore biodiversity in the Waikato region we need to do three things[4]:

1. Retain the ecosystems we still have - stop further loss through clearance, drainage, etc.

2. Restore degraded ecosystems - get rid of pests, stop pollution, harvest plants and animals sustainably, replant or return species that have been lost from the ecosystem, reinstate key natural processes, such as shade over small streams.

3. Reconstruct lost ecosystems - start from scratch to rebuild natural areas

As well as contributing towards the region’s climate goals through sequestration, ecological restoration has significant other (and in many regards more fundamental) benefits which include and are not limited to:

Restoring and in some cases re-creating natural ecosystems- primarily terrestrial and transitional (estuaries and wetlands) environments, but not excluding marine ecosystems

Restoring regional biodiversity

Improved water quality- including both surface and groundwater

Cultural restoration, especially for mana whenua with associated economic development (e.g. employment) opportunities

Waikato Freshwater Strategy estimates there were 523,000 hectares of marginal land in pasture in 2012. According to Land Use Capability classes, 76,000 hectares of class VII and class VIII land would not be suitable for production forestry but rather regeneration of native forests. The remaining 447,000 hectares of erodible class VI land could be either protection or production forests depending on economic considerations (size, location, proximity to mills and roads).

Waikato Progress Indicators

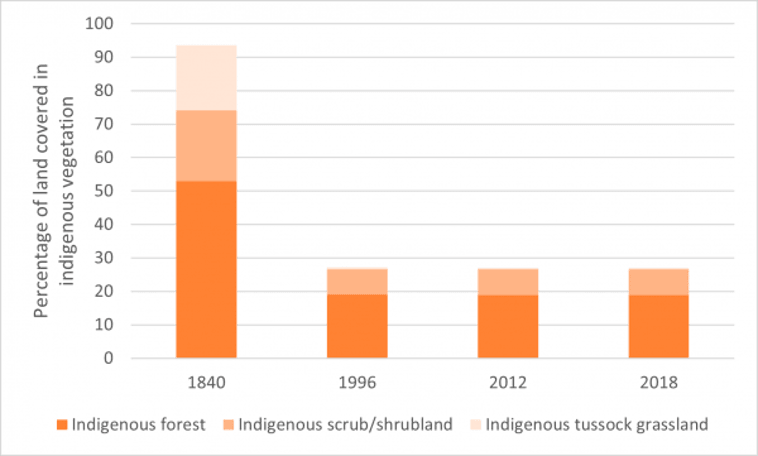

Before European settlement (around 1840), 94 per cent of the Waikato region’s total area of 2.4 million hectares was covered in terrestrial indigenous (native) vegetation, with the remaining 6 per cent being wetlands, bare rock, permanent snow and ice, or areas of Māori cultivation or inhabitation. Forest covered 53 per cent of the region. Scrub and shrubland or tussock grassland covered a further 41 per cent, mostly in areas where fires were frequent, or the land too wet or cool for forest.

Change in land use, for example to agriculture, plantation forestry and urban settlement, required clearing indigenous vegetation. Today around 648,905 hectares (27 per cent of the region’s land area) remains in terrestrial (land-based) indigenous vegetation cover, mostly indigenous forest (19 per cent of the region), and scrub and shrubland (8 per cent).

The greatest loss of terrestrial indigenous vegetation since 1840 occurred in the central Waikato lowlands, around Hamilton City and in the Waipa, Waikato, South Waikato and Matamata-Piako districts where fertile soils on gentler topography were suitable for livestock farming, or where the hills were cleared for pine plantations. Districts with more rugged hill country and extensive ranges, such as Taupō, Otorohanga, Waitomo and Thames-Coromandel have a greater proportion of indigenous forest, scrub and shrubland and tussock remaining.

Since 1996, the Land Cover Database (LCDB) records an estimated net loss of around 530 hectares of indigenous forest and 1240 hectares of indigenous scrub and shrubland, along with a gain of 46 hectares of indigenous tussock grassland. Between 1996 and 2012 the region lost terrestrial indigenous vegetation at an average rate of 85 hectares per year.

Between 2012 and 2018 the net rate of loss dropped to around 60 hectares per year. In that time the Land Cover Database reports a net loss of 89 hectares of indigenous forest and 312 hectares of indigenous scrub and shrubland. The actual amount of indigenous forest loss is considered to be much less (around 14 hectares) based on a visual assessment of the LCDB polygons that changed from indigenous forest to another land cover type against time-series Google Earth images. Many of the cleared areas classified as indigenous forest were either exotic forest or an indigenous scrub and shrubland class in 2012.

Today just over a quarter of the region’s land remains in indigenous vegetation, most of it forest. The areas that have lost the most indigenous vegetation tend to be coastal and fertile lowland areas, around Hamilton City and in the Waipa, Waikato, South Waikato and Matamata-Piako districts.

Between 2012 and 2018 there was a further net decrease of an estimated 356 hectares, with the greatest losses being manuka/kanuka and indigenous forest, partially offset by increased areas of broadleaved indigenous hardwoods and tall tussock grassland.

The amount of scrub and shrubland lost since 2012, through clearance or natural causes such as fire, was 619 hectares, but this was offset by a gain of 307 hectares, mostly through natural regeneration in areas of former exotic forest plantation.

By international comparison, Aotearoa | New Zealand has a large proportion of its land area legally protected for conservation purposes (32.9% in 2020).

[1] Biodiversity in Aotearoa - an overview of state, trends and pressures (doc.govt.nz)

[2] Goal 15 | Department of Economic and Social Affairs (un.org)

[3] Biodiversity in Aotearoa - an overview of state, trends and pressures (doc.govt.nz)

[4] Waikato-biodiversity-publication.pdf (waikatoregion.govt.nz)